Blog Titles

ToggleEphesus City Management

Administration of Ephesus City

How was the administration of the ancient city of Ephesus? How did the rulers of the city of Ephesus make decisions, and who made the decisions? What were the administrative buildings in the city of Ephesus called in antiquity? Did these people working for the city of Ephesus receive a salary?

How was the civil service in the city of Ephesus during the Hellenistic period? What duties did the officials in Ephesus perform? How many classes were civil servants in the city administration of Ephesus? You can find the answers to these questions in the city administration of Ephesus.

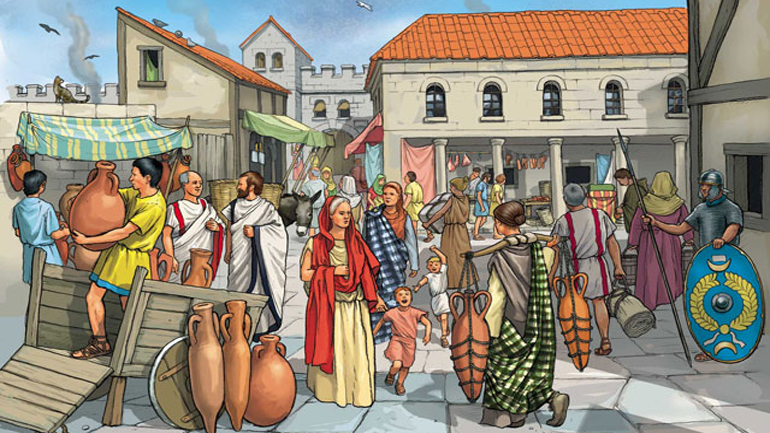

Ephesus Agora was the city’s life center. Although it is often known as a marketplace, it means a meeting place. Perhaps this is why Aristotle said that nothing should be sold in the agora, that there should be no workers or peasants, and that there should be another place for such work.

The presence of a state agora and a commercial agora in some cities, as in Ephesus, is a good example of this. The agora of Ephesus was the political, social, and administrative center of the city during the Hellenistic period. During the Roman period, it also served as a marketplace. However, in many Anatolian cities, there are Macellum that serve as marketplaces.

Agora is typically rectangular and has irregular spaces. It is usually located in the center of the city. If the city was a port city, the agora would be located close to the port.

It is surrounded by a stoa or peristyle. The main roads leading to the city of Ephesus would reach the agora.

Behind the stores in the Ephesus agora, there were shops, nearby fountains, administrative buildings, inscriptions in the square, altars dedicated to gods or heroes, statues of gods or heroes, and stalls of marketers and money changers (trapezius).

Large quantities of goods, including grains, ceramics, slaves, etc., were traded in the agora. In addition, vegetable and fruit sellers used to sell their food in the Agora of Ephesus.

There was a civil service in the Ephesus agora that was created to ensure that trade was done without fraud; this was called Agoronomoi. They checked the prices of the goods put on the market in the Ephesus agora, whether the weights of the scales were correct, and whether the money used in shopping was genuine. They would do this with their assistants, called Metronomoi.

The Management of the Ephesus

The story of the founding of Ephesus

In the Hellenic period, when a new city was established, the approval of the gods had to be obtained first. The priests were used for this. According to the culture that became almost a tradition in the 8th and 7th centuries BC, when the decision to emigrate was made, the people of the main city would choose a leader for the convoy.

This president, who was called the Founder (Oikist), first applied to the oracle of Delphi, Pythia, and asked where the city could be established. After receiving the prophecy from the oracle, he would go there with his people and establish the city. In this way, many ancient cities in the Mediterranean basin and Anatolia have had very interesting founding stories.

Management in Ephesus City

Cities founded during the Hellenistic period were small by today’s standards. Except for big cities such as Ephesus, Antioch, Athens, and Alexandria, most of the cities would not have a population of more than 10,000.

In the city of Ephesus, the people were divided into classes free citizens, children and spouses of free citizens, foreigners, freedmen, and slaves. Every free man who has completed the age of 18 is considered an adult and could participate in the election of members to the councils related to the administration of the city of Ephesus.

This group of people from Ephesus, who had the right to vote, was called Demos. To be eligible to be elected to the People’s Assembly (Ekklesia), he had to have completed his military service and completed at least twenty years of age. The city of Ephesus and other cities were enacting laws for the proper functioning of the people’s order.

It was the duty of the people’s assembly (Bouleuterion) to implement the decisions made in the city of Ephesus and to punish those who did not obey the laws. To be elected to the city council (Bouleuterion) or the municipal council (Prytaneion) in Ephesus, in addition to being a free citizen, it was necessary to be thirty years old and over.

The members of the people’s council (Bouleuterion) in Ephesus were elected by the Prytans from among the members of the people’s council. The Prtyans were chosen from among the members of Boule. The Prytans presided over the Bouleuterion for 36–39 days. The key and seal of the city of Ephesus were found in Prytanus of Ephesus.

Two beautiful examples of Prytaneion are seen in Ephesus and Priene. The People’s Assembly managed the city’s financial assets and acted as its spokesperson. It was also the duty of this assembly to build temples and decide on the erection of statues of famous people.

The Puritans were responsible for not extinguishing the fire of Hestia, the god of the hearth, who represented the eternal life of the city of Ephesus. Representatives from other city-states were hosted by the Prytans in Prytaneion.

Prytaneion Town Hall in Ephesus

After the Temple of Artemis, the Prytaneion, to the northwest of the state agora, was the most important structure in Ephesus. The holy fire of Hestia burned continuously in it. The Ephesians held political discussions here, entertained official guests, and held banquets; the Prytaneion had the function of Ephesus’ city hall.

The Prytaneion, with its square courtyard to the south and the Doric columns on its facade, looked like a temple. Immediately in front of the building is another, rectangular courtyard. The cult room of Hestia Boulaia is in the northeast part of the complex.

A two-room annex occupies the area west of this room. In each of the four corners of the cult room stood two columns formed in the shape of a heart, topped with decorated capitals.

The eastern section of Prytaneion was designed in tandem with the altar of Hestia in Ephesus. The holy fire, which never died out, burned on the altar. Because of the later buildings and additions, the altar was very difficult to discern in the initial excavations (1955). During these excavations, however, two famous statues of Artemis were found unexpectedly; these can be seen in the Ephesus Museum today. These statues demonstrate that the Prytaneion was not only a public building but also one of the most important sanctuaries.

The Pytanei were another group concerned with pretension. These were respectable citizens of Ephesus, both male and female, who were responsible for the holy fire.

The Pytanei stood in the service of the goddess of the hearth, Hestia, and were responsible for all cult activities.

This structure was first renovated in the third century BC, during the reign of Lysimachus; at this time, the Ephesians rebuilt the greater part of the structure and the columns of the facade in marble. A dozen years later, the building was extended by an entry court to the south, which had three facades and two entrances.

In the first half of the third century CE, heart-shaped double columns with decorated capitals were erected in the temple of Hestia. After an earthquake in the fourth century, the statues of Artemis were buried in the location in which they were found so that the adherents of the new religion would not destroy them.

The columns of the facade of the Prytaneion have Doric capitals. On these unfluted columns, the names of the courts are listed. Until the time of Augustus, these healers were monks of the Temple of Artemis in Ephesus. When the temple began to lose its prominence, the monks were reassigned to the Prytaneion.

In the first half of the third century CE, heart-shaped double columns with decorated capitals were erected in the temple of Hestia. After an earthquake in the fourth century, the statues of Artemis were buried in the location in which they were found so that the adherents of the new religion would not destroy them.

The Australian Archaeological Institute began excavations here in 1960. They restored the columns of the facade and, in part, re-erected them. The Ephesus Museum resumed excavations here in 1990; thus, the building, its annexes, and the other structures in the area are more clearly visible today.

In addition, in the city of Ephesus, there was an area where the Ephesians gathered as the city council or the people’s assembly (Ephesus Bouleuterion). This area is also the Odeon in Ephesus. Decisions about the people of Ephesus were taken here, and then they were announced to the people of Ephesus through inscriptions.

The task of the city council called the Boule, was to lease city lands, build public buildings, and maintain order and security in the city. Boule employed some clerks to fulfill these duties.

Agoronomos: The keeper of the agora was checking that the trade in the agora was done correctly and honestly.

Grammateus: Secretary of State, civil servant,

Gymnasiarchos: The official responsible for the gymnasium,

Perikoros: The official in charge of Ephesus’ relationships with neighboring states or cities.

Strategos: Commander-in-Chief

Kreupulos: The official in charge of the cemetery

Agonothetes: The official who organizes and referees competitions in stadiums, theaters, and in the city of Ephesus.

Those who were appointed as civil servants assumed this duty for a year and were not paid for their work. These people were considered the notables of the city, and some of them had fountains, baths, and aqueducts built and organized games for the benefit of the people of Ephesus to immortalize their names. Such people were called benefactors (Eurgetes).

Ephesus bouleuterion: Ephesus Odeon

The Ephesus Odeon, built into the south slope of Panayir Mount, is like a small theater. Its location north of the state agora and next to the Ephesus Prytaneion suggests that it also fulfilled the function of a bouleuterion (meeting place of the council of elders, or senate). An inscription tells us that Publius Vedius b. Antoninus built the Ephesus Odeon in the middle of the second century CE.

At the beginning of this excavation, archaeologists searched for traces of an earlier structure and uncovered various finds from the Hellenistic period. Except for the outer wall of the odeon, however, which was characteristic of the Hellenistic era, no other structural remains from this period could be recovered.

In the 1970s, the Ephesus Museum continued excavations and restorations, and by 1990, the Odeon had returned to its original form. The Odeon seats about 1500 spectators. It comprises three sections: the cavea (seating), the orchestra, and the scene. Two diazo mas and five radial aisles divide the semicircular cavea.

The audience could enter the odeon through two symmetrical vaulted entrances in the west and east. A narrow podium stands above the orchestra and in front of the richly decorated facade of the stage. Since there are no channels in the orchestra for the drainage of rainwater, the odeon must have been roofed. The roof would probably have been wooden.

Like many other structures at Ephesus, the odeon collapsed during a severe earthquake in the fourth century. The marble slabs forming the seats were reused in later restorations of other buildings.

These institutions in the Hellenic period in the city of Ephesus were completely under the control of the provincial governors (Proconsul) or his representative, Questor, who was sent to the city by Rome during the Roman period. Governors had the greatest administrative and military power in the states. He was the spokesman and had administrative and legal control over the entire province. All the expenditures of the province were approved by him.

Taxation and the collection of debts were under his control. He was authorized to convene the people’s assembly. The elections of administrators to be elected to the local governments were under his supervision and control. Provincial governors remained in the provincial center, while in non-provincial cities, the Questors fulfilled their duties.

This is how we can see the city administration in the ancient city of Ephesus. But there is a fact that should not be forgotten: the people elected to the people’s assembly in Ephesus were not paid. They were attempting to beautify their ideas as well as the beautiful city of Ephesus in which they resided. They have been very successful in this as well. The ancient city of Ephesus survived for about 1300 years.

When you come to the ancient city of Ephesus, you can learn new information by visiting the historical places known as the Ephesus Odeon, the Ephesus Municipality building (Ephesus Prytaneion), and the public assembly (Ephesus Bouleuterion) gathered in Ephesus. You can come to the city of Ephesus and become the current time traveler of the ancient city of Ephesus, which has a history of 2500 years.